In the early 50’s at the beginning of David Sheldrick’s renowned career as warden of TsavoEast National Park many events were taking place leading up to Tsavo’s very first Anti-poaching Campaign.

With further exploration of the Park it was soon discovered that there was serious poaching in the extreme north. The only means of access to this remote area, stretching north to Ithumba, lay in a long roundabout route through what was once known as the Wakamba Reserve, taking a full days travel. The obstacle isolating the north from the south of Tsavo East was the Galana River covering some 300 yards wide, which even today is still subject to severe flooding during periods of heavy rain.

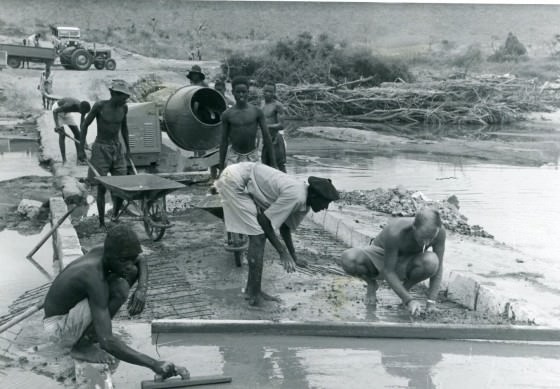

Action was desperately needed to open up the northern territories to reinforce the anti-poaching campaign and open communications, so it was decided that a crossing had to be constructed over the Galana. This presented a huge challenge to all involved as diverting the flow of this powerful and unpredictable river to enable concrete to be laid was no easy task, especially in the early 1950’s when materials and equipment were hard to come by and everything was predominantly constructed by hand.

Whilst overseeing the project, David Sheldrick tasked this difficult undertaking to John Lawrence, the Assistant Warden at the time, which took over a year to complete. Work on the crossing began when a suitable rock seam was located at a point just above Lugard’s Falls, which would form a base upon which the foundations could be laid. The Falls were named after Lord Lugard, who volunteered for the British Diplomatic Services in East Africa and passed through the area en route to Uganda in 1890. It is said that Lugard was bitten by a crocodile below the falls whilst cooling himself, which is why he received the honour of the Falls being named after him.

An eighteen foot fault in the rock seam near the south bank required the construction of a bridge to span the gap for work to continue, whilst great quantities of sand had to be removed by hand to expose the rock base for the buttresses. Men toiled day and night in shifts to bale out the water which seeped through the sand incessantly, in order to lay the necessary concrete foundations.

In addition to diverting the flow of the river, deep cuttings had also to be excavated through the quite sizable islands in midstream. Without the luxuries of cement mixers and stone crushers, which the Park’s meagre budget couldn’t afford, ballast for the project was broken by hand labour, which was constantly supervised by the newly appointed John Lawrence. It proved to be a long and drawn-out project, for every time the river came down in flood, work had to be abandoned until the water subsided again. Although over schedule the causeway represented a great stride forward in the development of Tsavo East, bringing the vast neglected Northern Area into the fold.

The causeway has since been widened, but the original structure still stands to this very day and is a vital artery for the DSWT’s field teams and the Kenya Wildlife Service, who, like the rangers before them, need a gateway to the north in order to combat the increased threat of poaching whilst facilitating the Trust’s second elephant orphans rehabilitation stockade and additional KWS initiatives. This was an engineering feat even by today's standards.