The Black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis), a living relic of a more pristine period in the earth's history, must surely be one of Nature's most interesting and sophisticated animals.

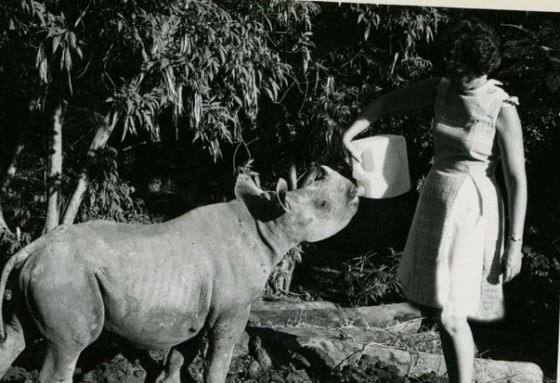

Having been called upon in my time to hand-rear over a dozen rhino orphans, three of them newborn, I know them well, and yet hardly a day passes that I am not astonished anew by these ancient animals.

Being a foster mother to any wild animal is a most enlightening experience. It affords a unique opportunity to learn and understand the animal in a very intimate way; to observe and study behaviour patterns and to fathom an ancient and complex mind. And, as time passes, so a window opens to reveal "the inside story" of the animal, and, in the case of a rhino, the inside story of an almost prehistoric creature that has been unchanged for millions of years.

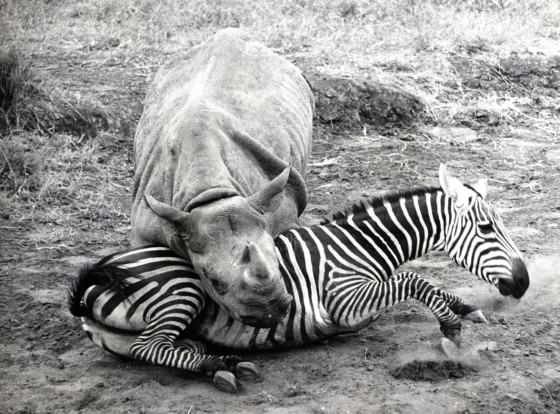

All wild animals, save the primates, amongst whom we are classified, have a genetic memory termed "instinct"; that mysterious "sixth sense" denied us humans. It is instinct that governs a lot of their actions, particularly matters important to survival, and instinct is particularly strong in more ancient species such as rhinos. Theirs is a hidden and complex world of scent and chemistry, their social system is complex, their body language and vocalizations subtle and their very rigid territoriality often confusing.

Most people mistakenly look upon rhinos as rather bad tempered misfits of the Animal Kingdom, an animal best avoided at all costs, whom no-one would really miss should it disappear from the face of the earth, and which perhaps is even overdue in being phased out as were those first animals, the dinosaurs. In fact, rhinos are one of the most maligned and misunderstood, for their ferocity stems only from persecution, attack being their instinctive means of self-defence. Rhinos respond to kindness quicker than any other animal. A wild caught adult can be tamed within just a few days simply by kindness. Once a rhino understands that here is a friend, and not a foe, you have nothing to fear, providing you, in turn, comprehend the role and significance of "instinct", and are prepared for the animal to switch rapidly into "auto-mode" should it become startled and feel threatened for any reason. At such times, a rhino moves with no conscious control over its instinctive reactions, and at such times, it is wise to make oneself as scarce as possible as quickly as possible!

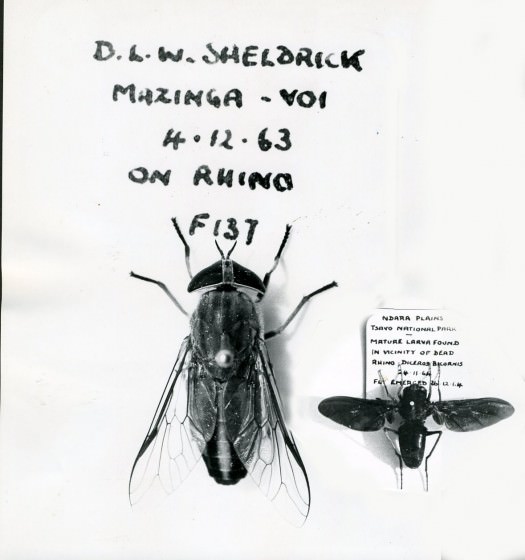

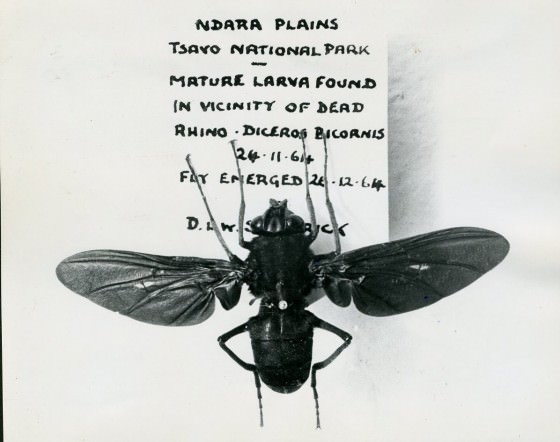

Through millennia, in conjunction with this ancient species, have evolved parasites that are specific to rhinos; for instance, the tiny flies known as Lyperosia that breed in their "middens" or communal dungpiles and which swarm and alight on the animal in soft clouds, particularly during the dry seasons. Another, very interesting fly known as Gyrostigma, resembles a wasp, and is a beautiful metallic blue with scarlet legs and head stripe, but devoid of mouth parts. Once this fly has hatched from a pupa in the ground, it must find a living rhino within its five day lifespan in order to begin its mysterious life-cycle anew.

My late husband, who was the founder Warden Kenya's giant Tsavo East National Park, and a famous Naturalist in his time, was one of the very first people to successfully hatch a Gyrostigma fly from a bot passed in the dung of a rhino. Even today, very little is known about this quaint and very beautiful insect, not only because it's lifespan is so short and it is so easily mistaken for a wasp, but also because it is crepuscular and as such very elusive, active only at dawn and at dusk. Most of its life cycle is spent in the form of a large and rather revolting looking beetle like "bot" that shares the rhino's food resource actually inside its stomach in a seemingly symbiotic relationship. Many rhinos harbour large infestations of bots, which might possibly become parasitic should the animal be in poor physical condition.

No-one knows how long a bot remains in the stomach of the rhino, but eventually it is passed in the dung to pupate in the ground with the first rains, but only if the rains are going to be substantial and conditions promise to be just right - otherwise the bots simply stay put until the next season, sometimes appearing briefly at the anal orifice to take a look around, and if conditions don't suit them, hurrying back in!

The eggs of the Gyrostigma fly, which are minute, oblong shaped and white, are laid in the soft striated indentations of the skin around the neck and head, and after some six days hatch into tiny "inchworms" no larger than the comma of a typewriter. At first it was assumed that these inch their way along to either the nose or mouth of the animal, but in fact, by observing them on our orphans, we discovered that they simply bore straight through the hide and from there somehow end up within the stomach itself.

Most rhinos also have lesions behind the shoulders and under the chin and stomach. These obviously itch and irritate, because they are rubbed against rocks and trees until they become open weeping wounds that stubbornly resist healing. The culprit for these lesions is apparently a filarial worm that again is specific to rhinos in Africa, but is known amongst horses in the Far East. The vector of the rhino filarial worm is thought to be another fly known as Rhinomusca which resembles the common housefly and again is specific to rhinos, feeding on their blood. Rhinomusca flies are often found in and around the filarial lesions, but also easily draw blood through the skin itself. Despite the ancient English saying - "a hide like a rhino", the skin of a rhino is extremely sensitive. Touch a rhino with a feather, and it will immediately respond. Rhino skin has an ample blood supply very close to the surface and, in fact, when the animal is in poor health, the skin "bleeds", coating the animal in a what looks like tar, but, in fact is dried blood.

Rhinos have myopic vision, but this is no handicap, but merely that they don't need their eyes in view of the sophistication of their other senses. For instance, they have phenomenal hearing. Our orphaned rhinos can detect the approach of another rhino half an hour before the animal actually becomes visible. A rhino's "come here" call to a loved one is no more than a soft exhalation of breath that is barely audible but which obviously carries far and is used mostly between mother and young. The rhino repertoire of louder sounds is equally as impressive - long drawn out snorts that resemble a nose blow which signify alarm, a mewing noise like a kitten which is a "wanting" sound, and a loud terrifying roar more akin to the voice of a lion when angry and prepared for combat.

Chemistry plays probably the most significant role within a rhino's life. By kicking their dung with the hind feet, they demarcate boundaries and territory and leave their specific scent trail on the ground for others to interpret their movements. By contributing their dung to the communal dungpiles, they alert all others within the community to their presence and establish their right to "belong". By squirting their urine against shrubs and bushes they advertise their rank and status through hormones, in the case of the females, also indicating estrous cycles and in the case of the males alerting others to dominance and rank which are important parameters for breeding. The memory of a rhino is also phenomenal. Having carefully and meticulously explored their surroundings only once, a new orphan can then take it at a gallop and never collide with any obstacle, moving swiftly and surely simply by memory and scent.

The role of rhinos within the environment is a very important one. The black rhino is essentially a browser, feeding mainly on shrubs, legumes and noxious weeds, many of which are poisonous to other animals. By cleanly clipping larger branches and twigs, they promote fresh soft shoots that sustain a large variety and number of other herbivores during the dry seasons and by ridding the pastures of toxic weeds, they inhibit their spread, thereby improving the grazing for others. They are a highly successful species in terms of Nature, moderate in their food requirements, and modest in their need for space. Were it not for the insane demand for their horn in the Far and Middle East, and indeed, for all their body components, which are enmeshed in myth and superstition, rhinos today would be as numerous as they were when the world was new. Only man's insatiable greed has pushed these wonderful animals to the very brink of extinction, so that today they teeter on the very edge of annihilation. And if they do go, the world will be the poorer for their passing and the demand for their horn will be one of many unforgiveable sins laid firmly at the feet of populous Far Eastern Nations.