The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust’s Mobile Veterinary Unit operating together with KWS spent the early part of the month translocating elephants from the Ngulia black rhino sanctuary in Tsavo West

The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust’s Mobile Veterinary Unit operating together with KWS spent the early part of the month translocating elephants from the Ngulia black rhino sanctuary in Tsavo West. The sanctuary which measures about 65Km2 had an estimated elephant population of 150 before a management decision was made to reduce their numbers in order to improve the performance of the rhino population. This number is far above the carrying capacity of the electrically fenced sanctuary and as a result there has been severe degradation of the habitat, compromising both the rhino and the elephants in the dry seasons.

In October 2005, attempts were made to drive the elephants out with a helicopter through selected areas of the fence, which had been brought down and camouflaged with bushes. The elephants stubbornly refused to go out and The Kenyan Wildlife Service decided to initiate other options. One of these options was to immobilise some, transport them and revive them outside the sanctuary close to watering points. To assess the success of this option, a small capture team comprising of two vets, a technician, four rangers and four drivers were sent to Ngulia between the 26th of June and 10th of July to undertake the exercise before a bigger translocation is planned. Thirty-eight animals were immobilised and removed from the sanctuary. This comprised of 35 bulls and a small family of three. There was no mortality.

Animals were located from a vehicle and either darted from the vehicle or on foot depending on the approachability and the vegetation cover. Those in open areas were darted from the vehicle while those in bushes were darted on foot. Darting was done with the Dan-inject CO2 propelled rifle which is more gentle and does not scare away the animals on dart impact. Etorphine Hcl at 18mg was used for the big bulls while 17mg was used for the smaller bulls and the family matriarch. Smaller doses were used for the smaller family members. Hyaluronidase was added to the immobilising darts to reduce the induction times.

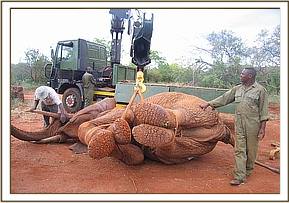

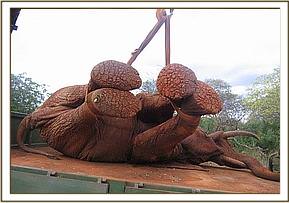

After the animal showed signs of narcotisation, the vehicles would close in slowly to enable a fast response immediately the elephant went down. Down time ranged from between 4 and 12 minutes depending on the dart site and averaged about 7 minutes. Once down, the animal would be processed for recovery while the vets and the technician monitored its stability and took necessary samples. Overheated animals were cooled with copious amounts of water especially on the top ear pinna. Animals were recovered by a lifting crane and transported while still immobilised to the release sites where they were revived.

The release areas were determined by the capture site. They were Rhino valley, Mtito-Ndawe junction, the Eastern end of Ngulia Airstrip and the Southern side of the sanctuary towards the Tsavo River. A few animals that looked compromised anaesthetically, those that took long to recover and those positioned badly on the transport lorry were released not far across the fence. We avoided transporting animals for long distances to avoid any complications that would arise when they were transported immobilised. Animals captured were then marked with numbers using white paint on their backs to enable identification and monitoring after capture before the paint disappears.

Report written by Dr. David Ndeereh. THE DAVID SHELDRICK WILDLIFE TRUST'S MOBILE VETERINARY UNIT IS FUNDED BY VIER PHOTEN